Every scaling company crosses inflection points where organizational approaches that worked at smaller scale become inadequate. Revenue milestones trigger transitions: the shift from founder-led sales to a professional sales organization, the move from informal financial management to structured FP&A processes, the evolution from ad-hoc hiring to systematic talent acquisition. These transitions are well understood and widely anticipated.

One critical inflection point receives far less attention: the moment when procurement transforms from a tactical activity into a strategic capability. For most companies, this threshold arrives at approximately $50 million in annual revenue, when purchasing volumes reach $10 million to $40 million annually. At this scale, the cost of unsophisticated buying becomes material, yet most organizations continue using approaches designed for much smaller operations.

The financial consequences of missing this transition are substantial and cumulative. Companies overpay on average by 20% compared to benchmarks, lack visibility into spend, maintain vendor relationships through inertia rather than evaluation, with manual procurement processes when automation would save significant time and reduce errors. These inefficiencies compound annually, eroding margins and consuming management attention that could be directed toward growth.

Why $50 Million Revenue Matters

The $50 million revenue threshold is not arbitrary. It represents the point where several procurement dynamics converge to create both opportunity and risk.

First, purchasing volume becomes significant in absolute terms. A company generating $50 million in revenue typically spends $10 million to $30 million annually on goods and services outside of direct labor. This includes direct materials as well as IT infrastructure and software, facilities and utilities, professional services, marketing and advertising, office supplies and equipment, insurance, and transportation. At $12 million in annual purchasing, a 20% cost premium versus best practice means $2.4 million in unnecessary expenditure—roughly 5% of total revenue flowing to inefficient procurement.

Second, organizational complexity creates coordination challenges. A $10 million company might have 30 to 50 employees making purchasing decisions collectively. A $50 million company has 150 to 300 employees across multiple departments and possibly multiple locations. Purchasing authority disperses across managers who lack visibility into company-wide spending. The marketing director negotiates with agencies, the IT manager selects software vendors, the facilities manager contracts with service providers, and the CFO handles insurance and banking relationships. No single person sees the complete picture or can identify redundancy and consolidation opportunities.

Third, vendor relationships transition from transactional to strategic. Smaller companies typically accept vendor terms with limited negotiation. At $50 million in revenue, purchasing volumes justify vendor attention and create negotiating leverage – but only if the company recognizes this shift and acts accordingly. Many organizations continue behaving as price-takers when they have become significant-enough customers to negotiate favorable terms.

Fourth, the cost of procurement inefficiency exceeds the cost of procurement capability. SMBs struggle to optimize spend without spend visibility tools, category expertise, and vendor management systems.

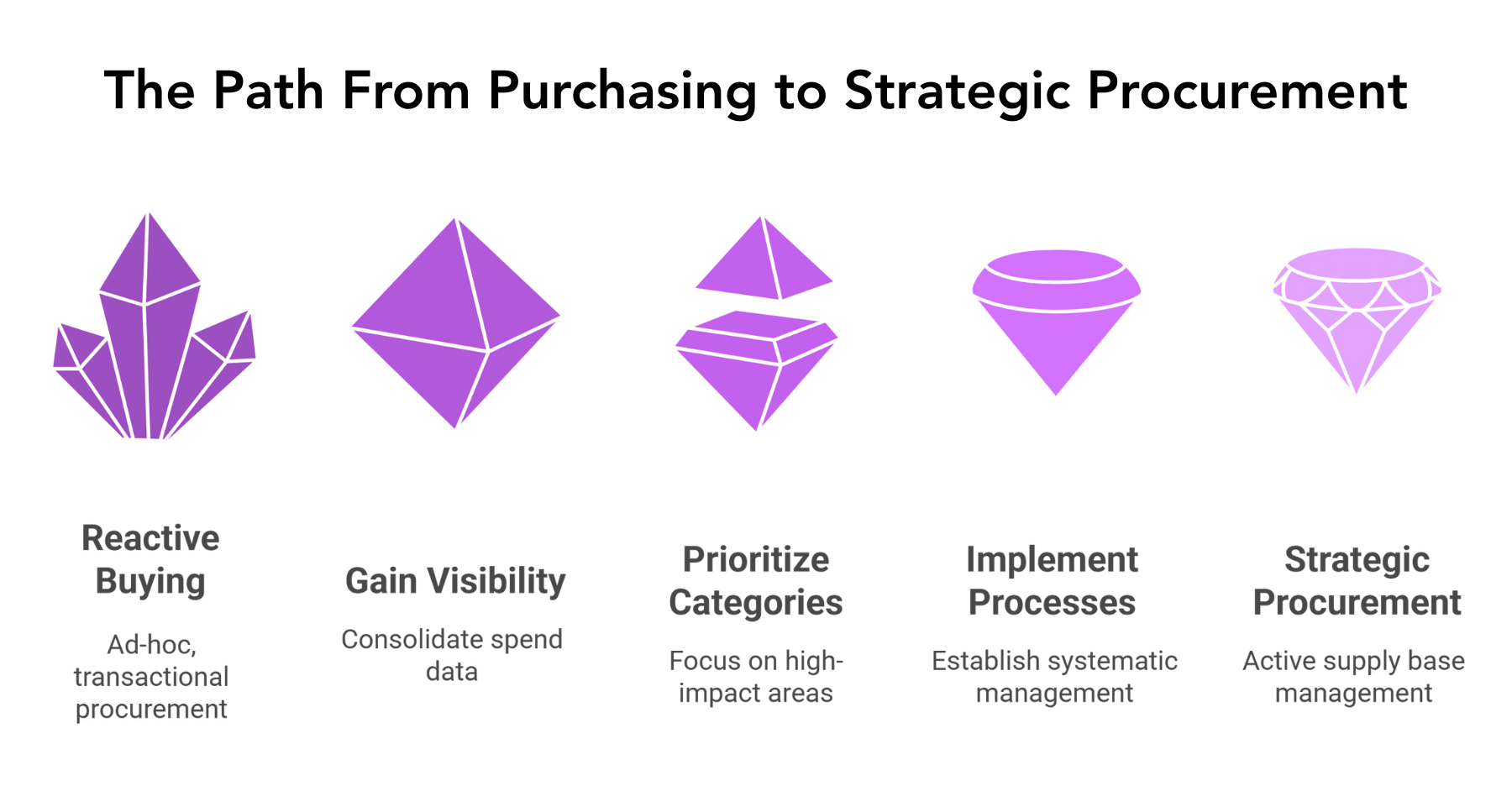

The path from reactive buying to strategic procurement requires visibility, prioritization, and process discipline. Mulberri’s platform helps portfolio companies move through each stage with speed, intelligence, and structure.

The Reactive Buying Trap

Companies below the strategic procurement threshold typically operate in reactive mode. Needs arise, someone identifies a potential vendor, basic requirements are communicated, a price is quoted, and if the price seems reasonable, the purchase proceeds. Contracts auto-renew annually. Price increases are accepted with minimal pushback. Vendor performance is not formally tracked. Alternative suppliers are rarely evaluated once a relationship is established.

This approach works adequately at small scale where purchasing volumes are modest and opportunity costs are limited. It fails systematically at larger scale for several reasons.

Pricing suffers from information asymmetry. Vendors understand their cost structures and target margins. Buyers typically do not know whether prices are competitive or inflated. Without benchmark data and competitive bidding, buyers accept pricing that may be 20% to 40% above market rates. The vendor has no incentive to offer best pricing proactively – they price to what the market will bear, and unsophisticated buyers bear high prices.

Contract terms favor vendors by default. Standard agreements include auto-renewal clauses, price escalation formulas, broad indemnification requirements, and limited exit rights. Buyers who accept these terms without negotiation surrender value unnecessarily.

Vendor proliferation creates administrative complexity and dilutes leverage. When every department selects vendors independently, companies end up with dozens of supplier relationships for similar goods and services. Ten employees might expense software subscriptions from eight different vendors when a single enterprise agreement would cost less and provide better functionality. Three departments might contract separately with logistics providers when volume consolidation would improve pricing and service quality. This is further proliferated across the PE firm’s portfolio of businesses.

Risk management suffers from lack of visibility. Reactive procurement means contracts expire unexpectedly, forcing rushed renewals on unfavorable terms. Vendor financial distress goes unnoticed until service disruptions occur. Insurance coverage gaps emerge because nobody maintains a comprehensive view of business risks.

The One-Person Procurement Department Problem

Many companies at the $50 million to $200 million revenue range assign procurement responsibility to a single individual – often an office manager, operations coordinator, or junior finance person. This person handles purchase order generation, vendor onboarding, invoice processing, and basic supplier communication. They are busy constantly but lack the time, authority, or expertise to optimize purchasing strategically. The result is a procurement function that handles transactions adequately but captures little strategic value.

The fundamental problem is scope versus capability mismatch. Strategic procurement requires category expertise across diverse spend areas: understanding IT hardware refresh cycles and software licensing models, evaluating insurance coverage structures and claims history, assessing logistics provider capabilities and rate structures, analyzing professional services firms and engagement economics. No single person can maintain deep expertise across these domains while also handling transactional procurement administration.

Organizations recognize this problem but often respond ineffectively. Some add headcount, hiring a second procurement person to share the workload. This provides operational relief but does not solve the expertise gap – two generalists are only marginally more effective than one at optimizing complex categories like software licensing or insurance programs. Other companies maintain the status quo, accepting procurement inefficiency as an inevitable cost of doing business rather than a problem with actionable solutions.

What Strategic Procurement Actually Means

Strategic procurement represents a fundamental reorientation from reactive purchasing to active supply base management. This shift requires capabilities that most mid-market companies lack internally.

Complete spend visibility is foundational. Organizations cannot optimize what they cannot measure. This requires consolidating data from accounts payable, corporate credit cards, purchase orders, and expense reports into a unified view. Every dollar spent, every vendor used, every contract term, and every renewal date needs to be visible in a single system. Most mid-market companies lack this visibility—they can tell you what they spent last quarter in aggregate but cannot break it down by category, vendor, or department with confidence.

Category expertise drives optimization. Different spending categories require specialized knowledge. IT hardware purchasing demands understanding of product lifecycles, vendor roadmaps, and residual value economics. Software procurement requires navigating subscription models, user licensing structures, and feature tier pricing. Professional services procurement focuses on rate structures, team composition, and engagement scope management. Generalist buyers cannot maintain expertise across these domains; meaningful optimization requires specialists.

Vendor management goes beyond relationship maintenance to performance measurement and continuous improvement. Strategic procurement means establishing performance metrics for each supplier relationship: delivery timeliness, quality standards, invoice accuracy, responsiveness to issues, and innovation contributions. Underperforming vendors receive structured feedback and improvement plans. Consistently poor performers are replaced. High performers earn expanded business. This disciplined approach requires systematic data collection and regular reviews that reactive procurement never implements.

Market intelligence provides competitive context. Strategic buyers monitor pricing trends, track new entrants, understand supplier financial health, and anticipate supply chain disruptions. They know when to time contract renewals to capture favorable market conditions and when to extend existing agreements to avoid unfavorable periods. They identify consolidation opportunities in supplier markets and leverage acquisition activity to renegotiate terms. This continuous intelligence gathering requires dedicated attention that operational procurement staff cannot maintain.

The Build, Buy, or Partner Decision

Organizations that recognize the strategic procurement inflection point face three options: build internal capability, purchase procurement technology, or partner with external expertise.

Building internal capability means hiring procurement professionals, implementing systems, and developing processes. For a $50 million to $100 million revenue company, a functional procurement team requires at minimum a procurement manager ($100,000 to $150,000 annually) and a procurement coordinator ($60,000 to $80,000). Add procurement software ($50,000 to $150,000 annually), spend analytics tools ($25,000 to $75,000), and contract management systems ($20,000 to $50,000). Total first-year cost approaches $300,000 to $500,000, with ongoing annual costs of $250,000 to $400,000.

This investment may make sense for companies spending $50 million or more annually on procurement. For companies at the $50 million to $200 million revenue threshold spending $10 million to $40 million on purchasing, the return on investment is marginal at best. The team lacks sufficient scale to develop deep category expertise. Technology costs represent large percentages of potential savings. Talent acquisition is challenging – experienced procurement professionals prefer larger organizations with established functions and clear career paths.

Purchasing technology alone provides limited value. Spend analytics tools show where money goes but do not optimize vendor selection or negotiate better terms. E-procurement platforms streamline requisition workflows but do not address category strategy or supplier performance. Contract management systems organize agreements but do not renegotiate unfavorable terms. Technology enables procurement excellence but does not create it—companies need expertise to translate data into action and tools into results.

Partnering with external procurement expertise offers a different value equation. Specialized providers have category experts across spending areas, serving multiple clients to achieve economies of scale. They come with technology platforms and market intelligence that individual mid-market companies cannot justify. They deliver results rapidly – typical implementations identify savings opportunities within just 10 to 30 days and begin generating returns within 30 to 60 days.

The financial structure aligns incentives effectively. Rather than fixed costs regardless of results, performance-based pricing ties fees to savings achieved or spending managed. Implementation costs are minimal compared to building internal capability. The company gains immediate access to expert-level procurement capability without the hiring challenges, overhead expenses, and time delays that building internally requires.

Recognizing the Signals

Several indicators suggest a company has crossed the strategic procurement threshold but has not adjusted its operating model accordingly.

The CFO cannot quickly answer basic questions about spending patterns: What are we spending on software annually? How many logistics providers do we use? When do major contracts renew? What percentage of spending goes through formal purchase orders versus credit cards? If these questions require days of data gathering rather than immediate answers, procurement visibility is inadequate.

Department heads complain about procurement bottlenecks and circumvent formal processes. This signals that existing procurement approaches create friction without delivering value. When users avoid procurement rather than engaging with it, the function has become a compliance obstacle rather than a value-enabling capability.

Vendors initiate renewal conversations weeks before contracts expire, forcing rushed decisions without competitive evaluation. Strategic procurement means anticipating renewals months in advance, evaluating alternatives systematically, and negotiating from positions of strength rather than time pressure. Reactive renewals signal inadequate contract management.

The person handling procurement spends time on transaction processing rather than strategic activities. If procurement staff are focused on purchase order creation, invoice matching, and vendor setup rather than category strategy and contract negotiation, the function operates tactically regardless of company scale.

Similar goods and services are purchased from multiple vendors at different prices. When office supplies come from three different distributors, software subscriptions proliferate across departments, and professional services are contracted independently by every manager, procurement lacks consolidation discipline and volume leverage.

The Cost of Inaction

Companies that cross the strategic procurement threshold without adapting their approach pay an ongoing tax on inefficiency. The financial impact is both immediate and cumulative.

Immediate costs come from pricing disadvantages, unfavorable contract terms, and operational inefficiency. A $50 million revenue company spending $12 million annually on procurement that pays 20% more than necessary wastes $2.4 million per year. This flows directly to reduced profitability – dollars that could fund growth instead go to vendors.

Cumulative costs emerge from compounding inefficiency, which is exacerbate across the portfolio. Software subscriptions that auto-renew with 5% annual price increases compound over five years to 28% higher costs. Service contracts that roll over without renegotiation accumulate unfavorable terms incrementally. Shadow IT proliferates as departments work around procurement constraints, creating technical debt and security risks that require expensive remediation later.

Opportunity costs represent value not captured. Money overspent on procurement cannot fund product development, market expansion, or talent acquisition. Management time consumed by vendor crises and contract renewals does not go toward strategy and execution. The attention that procurement inefficiency demands is attention unavailable for activities that drive growth and competitive advantage.

For private equity-owned companies, these inefficiencies directly impact valuations. EBITDA improvements from procurement optimization multiply at exit- every million dollars in annual savings creates $8 million to $10 million in enterprise value at typical exit multiples. Conversely, inefficient procurement that depresses EBITDA reduces exit proceeds proportionally. PE firms that recognize this dynamic implement systematic procurement approaches across portfolios; those that do not leave substantial value uncaptured.

Making the Transition

Transitioning from reactive to strategic procurement does not require wholesale organizational disruption. The shift happens incrementally through deliberate choices about visibility, expertise, and vendor management.

The first step is establishing baseline visibility. Companies need to understand current spend before they can optimize it effectively. This means consolidating data from all payment sources, categorizing expenditures, and identifying major vendor relationships and contract terms. Partners with specialist analytics tools produce a baseline in days, which reveals immediate opportunities – duplicate subscriptions, unused licenses, contracts rolling over at unfavorable terms, and pricing that exceeds benchmarks substantially.

The second step is addressing high-impact categories. Rather than attempting comprehensive procurement transformation simultaneously, strategic organizations prioritize. Software spending typically offers quick wins – license optimization, subscription consolidation, and vendor renegotiation deliver 15% to 25% savings within 30 to 60 days. Professional services, IT hardware, and facilities expenses follow as next priorities. This sequenced approach generates early returns that fund ongoing optimization.

The third step is implementing systematic processes for ongoing management. This includes contract calendars that anticipate renewals months in advance, supplier scorecards that track performance consistently, and spend analytics that identify anomalies automatically. These processes need not be elaborate – simple systems maintained consistently outperform sophisticated approaches applied intermittently.

The execution challenge is balancing thoroughness with speed. Procurement optimization creates value rapidly but only if implemented decisively. Organizations that assign the initiative to procurement staff as an additional responsibility alongside operational duties generate limited results. Those that utilize specialist partners capture value within quarters rather than years.

The $50 million revenue threshold is not a destination but a starting point. Companies that recognize this inflection point and adapt their procurement approaches accordingly gain sustainable cost advantages, operational resilience, and management bandwidth. Those that maintain reactive purchasing approaches designed for smaller scale continue paying the inefficiency tax indefinitely. The transition requires deliberate choice and focused execution, but the return on investment is substantial and recurring.